Year of the Bear

The bear is an important animal to many northern peoples, if not even sacred. Some peoples even claim descent from the bear and think of it not only as a holy entity, but also their tribe's ancestor. The Finns also have lots of customs that suggest that the bear is highly important in the traditional Finnish religion. Perhaps the most known custom relates to the bear wake (karhunpeijaiset), in which the fallen bears soul is returned back to it's birthplace in heaven. Besides this, there are customs related to the bear through the entire year, such as the time of the release of the cattle in spring. In this writing, we will reveal traditions related to the bear, based on which we can justify also Midsummer, in this case 13th of July, to be a holy day in the bear cycle of the year.

On the bear

In this writing, we use the word bear to refer to the brown bear (Ursus arctos) of the bear family (Ursidae). The bear is the largest predator of Europe and it is the national animal of Finland. The range of its subspecies is wide nowadays, from Northeast Iberia all the way through Eurasia to west of North America. Formerly bear subspecies were living also in modern-day Mexico and in the Atlas mountains in Noth Africa. The subspecies that can be found in Finland lives also in the mountains of Southern and Central Europe, but also in the taiga (the boreal forest found throughout the high northern latitudes, between the tundra and the temperate forest).

Already Aristotle in his History of Animals wrote that the bear is an omnivore: around one third of its diet consists of various meat, otherwise it also eats plants, roots, berries, honey and nuts. From spring to autumn, the bear gathers tens of kilograms of fat that it uses during the winter. The bear enters its hibernation around October-November. A few weeks before hibernation, the bear chooses its den and just before hibernation it empties its bowels. The bear's hibernation isn't as deep as winter torpor, which is why the bear might wake up from its sleep if its energy resources have emptied ahead of time. The female bear gives birth during hibernation. The bear also reacts to its surroundings during hibernation, for example, when the snow melts and flows into the den. Usually the bear wakes up from its den around March-April.

The word karhu 'bear' is a taboo expression from the word karhea 'coarse', referring to the fur of the bear. The bear has over 200 different names, which tells of the significant role of the bear in Finnish folklore. Few other examples of the bear's names are Mesikämmen ('Honeypaw'), Källeröinen, Otava ('Big Dipper'), Suuri herra ('Great Lord'), Tätini poika ('Son of my aunt'), Metsä ('Forest'), Metsähippa, Metsäläinen ('Forester'), Metsän hevonen ('Horse of the Forest'), Metsän kuningas ('King of the Forest'), Metsän hiisi ('Goblin of the Forest'), Metsänpitäjä ('Keeper of the Forest'), Hongattaren poika ('Son of Hongatar'), Metsän ukko ('Old Man of the Forest'), Metsän vanhin ('Elder of the Forest'), Lintunen ('Little Bird'), Lullamoinen, Luukyrpä ('Bone Dick'), Musta mulkku ('Black Dick'), Kontio, Metsän omena ('Apple of the Forest'), Kultahammas ('Goldtooth'), Jumalanmies ('Man of God'), Kouvo ('Forefather'), Ukko ('Grandfather'), Äijä ('Grandfather'), Suuri jalka ('Bigfoot) or just Hän ('He'). The original name of the bear was oksi. This name has been preserved in Livonian (okš), South Estonian (ot́t) and Erzya (ovto), going back to West Uralic *okti. The word stem hasn't been preserved in the Finnish written language, but in the East Finnish dialect of Savo it has survived in the diminutive form ohto, that developers of the written language in the 19th century thought (falsely) would go back to the Proto-Finnic form otso (parallel to mehtä ~ metsä 'forest'), which then stayed in the standard language. Nevertheless, the many different names of the bear speaks of the strong and essential position in the Finnish world view.

According to Finnish poems, the bear was born in heaven "by the moon, next to the day, on the shoulders of Otava", from where it was lowered down to earth "in a golden cradle, with silver cords". Similar tales are also presented by our Ob-Ugric kindred peoples, the Khanty and Mansi. It has also been said that the bear was born "in the darkness of Pohjola". The skull of the bear is hanged on a pine branch at the end of the ceremonial funeral of the bear (peijaiset), to the care of its mother Hongatar. These different explanations don't rule each other out and in a certain poem there is a mention of the bear that "Ilmarinen is your father, Hongatar is your mother".

The genderness of the bear is revealed in many traditions regarding the worship of the bear.

The female bear is said to leave men be when it encounters them in the woods, and vice versa when a male bear sees a woman. Yet, the bear has been mostly thought to be male, because it could sometimes also be "shamed". If a woman met a bear in the woods, she got the bear to run away by showing her behind to it. In Carelia, this was called harakointi ('crotching') and it was performed by women who had given birth to at least five children, because she who had given birth five times had a vittu, a magically strong genital. The lady protected the cattle by standing with her legs spread on top of the barn door so that the cattle would walk beneath her when the cattle was let out in spring. This powerful female genital compares as a mirror image of sorts to the bear's manliness, as in the bear's taboo names "Luukyrpä" ('Bone Cock') or "Musta mulkku" ('Black Dick'). This manliness could be seen especially in customs related to the bear hunt: before the hunt, men were not allowed to be in contact with women. In the Saami culture, men were not allowed to approach their women the night before the hunt and three nights after the funeral, the leader of the hunt had to be five days separated from his woman. Also in stories about the origins of bear clans, it is the union a male bear and human woman.

Festivities and tales of the bear around the world

In it's living habitat, the bear is usually the biggest predator and therefore it has affected the worldview of many nations. The bear is part of many stories about the world and the stars, particularly the Big Dipper. A ritual behaviour dedicated to the bear is present not only among the Finns, but also among their kindred peoples such as the Saami, Ob-Ugrians, as well as the peoples of the Pyrenees, the Nivkh of Siberia, the Ainu people of Hokkaido and the Indians of North America. In this article by ritualistic behaviour we mean various customs depending on cultural contacts, the dominant religion and general history, the common basis being that the bear is seen as holy and sacred. Among many nations who have preserved customs related to the worship of the bear, the bear has had a close connection to that nation. The bear has been their forefather, primordial progenitor of their family or clan.

Below some examples are introduced of customs and traditions regarding the bear, especially describing the peoples of the Pyrenees, peoples in the region close to the Okhotsk Sea and our kindred people, the Saami and Ob-Ugrians.

The Pyrenees

The Pyrenees mountain range separating the Iberian Peninsula from the rest of Europe is one of the few areas in Western and Central Europe where the bear still lives. The peoples inhabiting the Pyrenees are not only the Pre-Indo-European Basques, but also the Romance Spaniards, Occitans, French and Catalans. One of the most popular folktales of these nations has been the story of John the Bear (Spanish: Juan del Oso; Occitan: Jan de l'Ors; French: Jean de l'Ours; Catalan: Joan de l'Os; Basque: Juan Artz). The general storyline is as follows: the hero is half-human, half-bear. His weapon is an (iron) staff and on his way he meets two or three companions. At a castle, the hero defeats an opponent and follows him into a hole, where he finds the underworld, from where he rescues three princesses. His companions abandon him in the hole and take the princesses for themselves. The hero escapes, finds the companions and defeats them. After challenges set by the king, he married the most beautiful of the princesses. (The story is also known in its local versions among, e.g., the Russians and the Avars of the Caucasus, where the hero is called 'Ivan, The Bear's Ear'.) There are other stories related to this story worldwide, and similar elements can be found, for example, in the Old English story of Beowulf (Beowulf means 'bee-wolf', which was an Anglo-Saxon poetic alliteration for the bear). French researchers Daniel Fabre and Violet Alford have drawn attention to the similarities between the story of John the Bear and the customs of traditional bear festivities in the Pyrenees. The Pyrenean bear festival is traditionally timed either between the first week of December (Andorra's "last Ordino bear festival") and the carnival period before the Easter Lent (February-March). Traditionally, the celebration was held on Candlemas Day (2th of February). Different regions have their own local characteristics, but the celebrations have a common structure of events. The festival is practically a comedic account of bear hunting. The performance includes dancing, pantomime and a festive meal.

The symbolism of the bear festival in Iberia is connected to the cycle of the year. The awakening of the bear in late winter around Candlemas represents the arrival of spring and the departure of bad weather, as well as the rebirth of life in the mountains. Candlemas is the absolute end point of the Christmas season and therefore the first festival of spring. The bear is the king of animals and the ruler of the underworld, releasing the souls of the deceased with the spring breeze.

The bear is also strongly associated with fertility and sexuality. After all, the bear rises from its den in spring to eat and mate. In many plays of the bear festival in the Pyrenees, the bear specifically chases women, as the local stories of the area also tell. Only the felling of the bear at the end of the plays enables the control of primitive spirits and chaotic forces that awaken during spring towards the new summer.

The Nivkh and Ainu

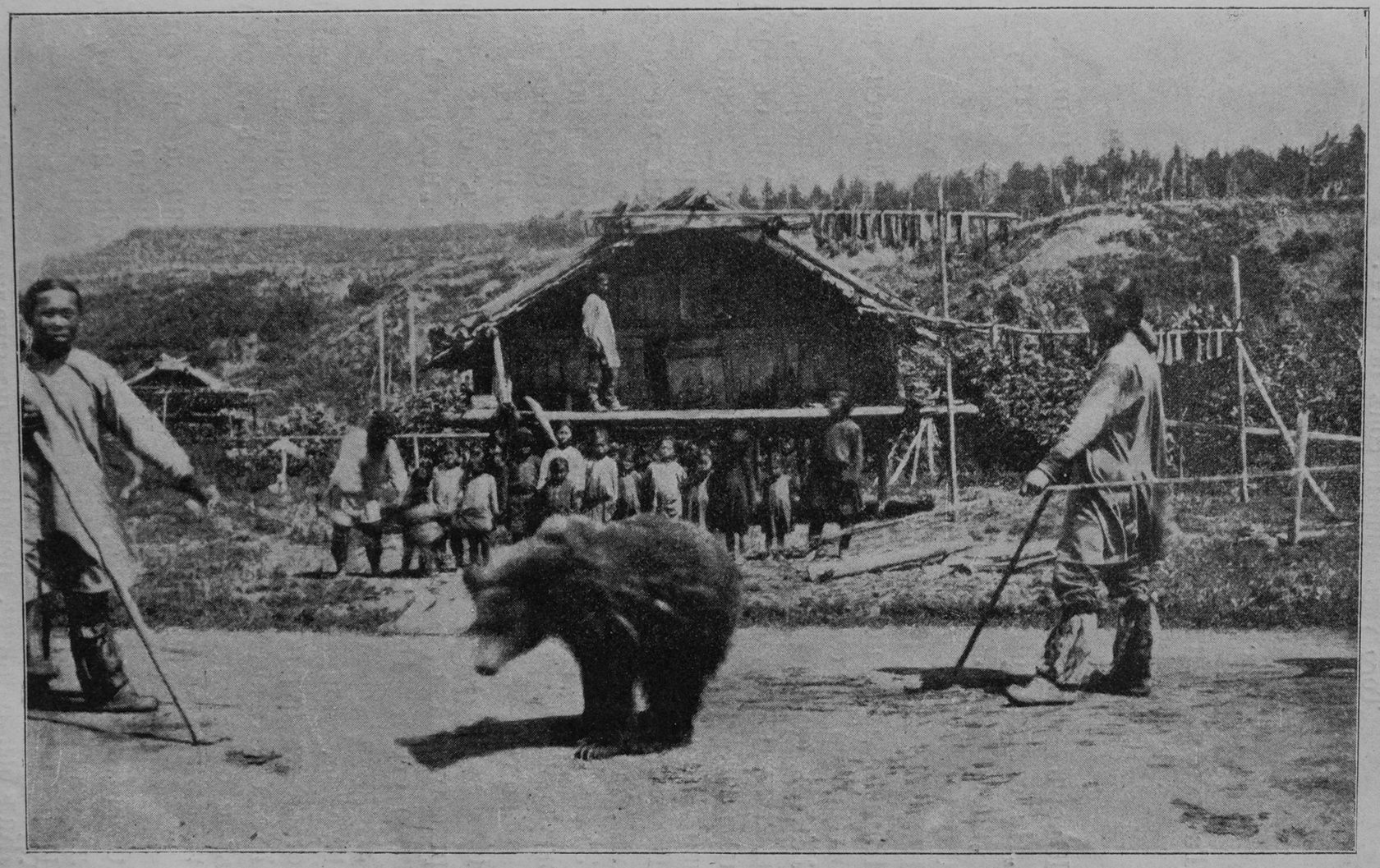

The Nivkh have traditionally lived in the lower estuary of the Amur River and opposite in the northern part of Sakhalin Island. The Ainu have lived not only in Hokkaido, but also in the southern part of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. Neither the Nivkh nor the Ainu have any certain linguistic relatives in modern times, nor are they related to each other. Prehistorically, the Nivkh and the Ainu have interacted with each other. Japanese and Russian researchers connect the prehistory of the Ainu with the Okhotsk culture, which spread from northern Hokkaido to Sakhalin, the Kurils, and northern Honshu. Traces of bear worship have been found in the remains of the Okhotsk culture, in contrast to the remains of the Jomon culture that spread from the south. Bear festivities among the Nivkh and the Ainu that have survived to modern times contain many common features, which is why they have been considered to represent a common origin.

One of the most important annual festivals of the Nivkh was the bear festival, which was organized either in January or February, depending on the tribe. The bear was caught and brought to the village, where the women of the village raised it for several years. Ancestors and Gods in earthly form are personified in the bear. At the celebration, the bear was dressed in a ceremonial outfit and a festive meal was organized in its honour, so that when the bear returns to the Gods, it would show its favour to the tribe. After the meal, the bear was shot with an arrow and eaten ceremonially. Two dogs were also sacrificed at the feast. At the end of the celebration, the bear's head and harness were hung on a frame resembling a body. In this way, the bear returns to the Gods of the mountains happily and blesses the Nivkh forests plentiful.

In the Ainu religion, the bear is not only the God of the mountains, but also the King of the Gods. The bear's name in Ainu is kamui, which literally means "god". Among the Ainu, the name of the festival corresponding to the Nivkh festival is iomante, which literally means "sending away". Corresponding to the Nivkh tradition, the Ainu caught a bear cub from its winter den after killing the mother bear and raised the cub in the village. When it was time to send it away in the autumn, the two-year-old bear was taken from its cage and taken to the center of the village, where it was tied to a post. The men of the village each took turns shooting the bear with arrows until one of the villagers killed the weakened bear with a neck shot. After this, the bear's throat was cut and the blood was drunk. The bear was skinned and the meat was distributed among the villagers. Finally, the bear's skull was placed on the tip of a spear and wrapped in its fur. Iomante lasted three days and three nights for the bear to return to its home in the right way. So the bear was sent back to the realm of the Gods, where it took human form again and told the other Gods how well it was treated in the human world.

Uralic peoples

The closest to Finnish customs are the knowledge and traditions related to bear hunting that have been preserved among our kindred peoples. Here is a brief introduction to Saami bear funerals.

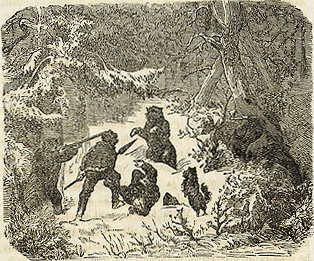

There are records of the Saami bear funerals, but this custom is no longer followed. The Saami bear hunt took place in late winter and the person who found the bear's den led the hunt. There was also a witch (noajdde) in the hunting group and the head of the group had a brass ring on the end of his staff. After the kill, the participants hit the bear's body with birch branches, one of which was folded into a ring around the bear's lower jaw, where the person leading the hunt pulled three times. When the group returned to the winter village (sijdda), the women spat alder bark liquid on the faces of the hunters and painted rings around their hands, drawings on their chests, and crosses on their heads with the liquid. During the preparation of the festive meal prepared for the bear, women were not allowed to be with the men in the same hut, which was set up separately for the funeral. Women's heads had to be covered and they could only look at the leader of the group through a brass ring. After three days of preparations, the bear skin was stretched out in the center of the banquet hall and was given gifts such as tobacco and food. After the apology, they had dinner. After the meal, copper chains were attached to the copper ring and this entirety was tied to the bear's tail. The ring was then given to the men, who buried it with the bear bones. The skull was hung high on a tree so that the animals would not get it and the bear's soul would be reborn. Finally, the skin was placed on a stump and the women of the bear hunters, blindfolded, shot arrows into it. After three days, the men cleaned themselves, e.g., by washing with lye and running around the houses imitating the grunting of a bear. After this purification, the men were allowed to continue their everyday lives.

Finnish karhunpeijaiset

There is information about the Finns' karhunpeijaiset as early as the 17th century, when on 15 July, 1640, Bishop Rothovius preached at his inauguration of the Turku Academy, slandering the Finnish bear traditions (and thus recording the first description of the bear funeral for posterity). From the beginning of the 18th century, the most complete preserved description of the bear funeral, (karhunpeijaiset) is "Couvon päliset eller Häät" in the anonymous writing known as the Viitasaari text. Christian Salmenius's 1754 work "On the history and economy of Kalajoki and Ostrobothnia" also contains a description of the karhunpeijaiset. Based on the earliest descriptions, the course of events for karhunpeijaiset is as follows: the bear was killed in the forest, after which itwas brought to the village. After this, a day was agreed on when Kouvo's wedding would be celebrated. In honour of the bear, a boy was appointed as the groom and a girl as the bride, and beer, liquor and "the deceased's own meat with pea soup" were enjoyed at the celebration. The bear's head on a platter and the bride and groom were placed at the end of the banquet table. After the meal, poems and requests were sung. Finally, the men removed the teeth from the bear's skull to share among those who participated in the hunt.

The second part of the funeral continued as a procession to the bear skull pine, the bridal couple first, then the bearer of the beer horn, the singer, the carrier of the bone platter and finally the rest of the participants. Once there, Hongatar, the bear's mother, welcomed the new bear to her family with the singer's mouth. At the pine, the bones were buried at its base and the skull was hung up, looking east towards the sunrise.

Bear anniversaries

The bear has been remembered not only in the heart of winter at the karhunpeijaiset, but also

throughout the year.

The descriptions of the celebrations above about the karhunpeijaiset are related to the winter time. Winter bear funerals, based on various examples from around the world, suggest that it is precisely the festivals practiced in winter that are the most essential layers of bear worship. However, in the Finnish tradition, bear-related celebrations have been preserved in other seasons as well. Looking at these holy days as a whole, one can talk about the Year of the Bear.

The pre-Christian year was divided into two, the summer and winter halves. In Finnish tradition, the designations of the half-term days have been preserved: Summer Nights at the first nights of the summer half (12-14 April), Winter Nights at the beginning of the winter half (12-14 October). Between these halves are Midwinter (13 January) and Midsummer (13 July). The year was thus divided into 13-week periods, according to which the passage of time was measured before ecclesiastical calendars and almanacs, using the system popularly known as week count. In the Estonian tradition, the names of Midwinter and Midsummer have preserved an even stronger connection to the bear: Midwinter is korjusepäev 'bear den day', Midsummer is karusepäev 'bear day'.

The essentiality of the winter bear festival is indicated not only by the bear hunt, but also by

numerous proverbs about the bending of winter's back during the middle of winter. During the winter season, from autumn to Talvi-Matti (24 February), the bear could be talked about with its real name while it was laying down in its winter den. The bear turned on its other side on Midwinter, saying "midnight, hunger in the gut". Depending on the region, Midwinter has been Heikki's Day (19 January) or Paul's Day (25 January), in northern Finland even Matti's Day (24 February). The names and backgrounds of these days themselves point to a Christian influence, and Kustaa Vilkuna concludes that the tradition of these days is connected to the old Midwinter day, that is, 13 January.

In spring came the most important event in animal husbandry, that is, leaving the cattle out on pasture for the first time. Like all actions that are made for the first time, this event too is a sacred moment that requires special measures. The best time to leave the cattle out was the waxing moon, when the milk supply increases, but also the direction of the wind, for example, influenced the choice of time. When Etelätär, the Goddess of the South Wind, was on the move, the cattle was the most protected. The spells said during cattle leaving have asked precisely Etelätär to protect the cattle.

However, the protection of livestock has been requested from many different deities with different emphases. Not only Etelätär, but also Suvetar (the Goddess of Summer) and Ukko Ilmollinen (Sky Father) himself have been asked for help in protecting the cattle "this great summer". Cattle traditionally grazed in the forest, which is why the folk of Tapio - Tapio (God of the Forest), Tuometar (the Goddess of the Bird Cherry), Pihlajatar (the Goddess of the Rowan), Katajatar (the Goddess of the Juniper), etc. - have also been asked to protect the cattle while they graze as guests in Tapio's kingdom, so that the cattle do not fall under the forest's wrath. Cattle protection has been requested not only against wrath of the forest, but also against beasts, which is why also the mother of beasts was turned to. Loveatar, or Louhi (the Crone of the North), is mentioned as the mother of wolves in most spells, but she is also mentioned as the mother of the bear in some spells. In the majority of spells, however, the mother of the bear is Hongatar, the Goddess of the Pine. Of course, it is possible that they are the same goddess, because one variant of Hongatar is "Hongas, Lady of the North". However, this possibility will not be discussed in this article, as the topic requires its own consideration. One way or another, when talking directly to the bear, reconciliation has also been requested for the summer, as you can see from the excerpt from Kustaa Vilkuna's example of the cattle's spring poem:

Kesän tullen, suon sulaen, (As summer comes, the swamp melts,)

lätäköiden lämmitessä, (as the puddles heat up,)

kanervoien kukkiessa (when the heather is in bloom,)

työnnän lehmäni leholle (I push my cows to the pasture,)

hatasarvet haavikolla, (stud horns to the aspen forest,)

missä pyy pesän pitävi, (where the grouze nests,)

kana lapsen kasvattavi. (hen raising a child.)

Metsän ukko halliparta, (The old man of the forest with a grey beard,)

Kummun kultainen kuningas, (The golden king of the mound,)

tee tämä sula sovinto, (make this tender reconciliation,)

kesärauha rapsakaamme (let's enjoy the summer peace,)

tänä Jeesuksen kesänä (this summer of Jesus,)

Luojan suurena suvena. (great summer of God.)

Ohtoseni, lintuseni, (My bear, my bird,)

anna rauha raavahille (give peace to the neat,)

sontareisille sovinto. (frith to the dung thighs,)

Kun sa kuulet karjan kellon, (When you hear the cattle bell,)

tunge pääsi turpehesen, (stick your head in the turf,)

työnnä kynsi karvoihisi, (stick your nail in your fur,)

jottei hampahat hajoaisi, (lest the fangs fall apart,

eikä leuat lonkuaisi. (and your jaw drop.)

Temporally, the release of the cattle is originally related to the days of the Year of the Bear, namely the Summer Nights. On these days, the shepherds blew horns to shut the wolf's mouth, boys asked girls for a drink, magic was done to find bird's eggs, and it was counted that there would be a hundred days until the rye was cut. Due to the uprooting of tradition practiced by the Christian church, many customs have been transferred to Christian celebrations, such as Easter or "the old Summer Nights", that is, the days of Yrjö (Jyri), Alpert and Markku. According to the current calendar, the old Summer Nights are 23, 24 and 25 April, but it must be remembered that Sweden did not switch to its current Gregorian calendar until 1754, when the holidays were brought forward by 11 days. In other words, some localities continued to celebrate the summer holidays according to their calendar date, that is, 12-14 April, while in other regions their celebration coincided with the mass of Christian saints. The Christian Church, however, encouraged at a very early stage to mark the day of the cattle release with a date suitable for the Christian saint calendar, which is reflected in the cattle spells by turning specifically to Jyri (St. George), so that he would "bind his dogs", i.e., wolves and bears.

In the Year of the Bear, the significant day during summer is 13 July. In the ecclesiastical calendar, this day has been the day of Marketta (Saint Margaret of Antioch) in Finland and Estonia, exceptionally in the entire Christian world, because elsewhere the day iss July 20. The day has traditionally been the start of haymaking, and the rune staffs have a rake to mark the day. Kustaa Vilkuna explains the emblem of the rake as originating from the emblem of the Saint Margaret, but simply the timing of the most important work of the season, haymaking, around the time of day is also a natural explanation. The day has also traditionally been the midsummer, as the explanation of the sign of the day is in the 1672 rune staff from Lapland. As mentioned, Marketta's day was placed on 13 July not only in Finland, but also in Estonia. As also mentioned above, 13 July in Estonian is also called karuse päv 'day of the bear', karo püha 'holiday of the bear'. In Estonia, not only the pre-Christian name of the day has been preserved, but also the customs related to it. The Day of the Bear has been an important holiday when people had to be and live in a way that was pleasing to the bear, otherwise the bear would attack the livestock. Thus, work was generally avoided, and there is also lore from Finland about the Marketta's church mass, i.e., celebrating the day as holy. In Estonia, the name of July has also been karusekuu, 'bear moon'. Kustaa Vilkuna convincingly gives the reason why the Christian Marketta was identified with the Bear. The original celebration of the day was to repel beasts with holy behavior, which suited the story of a saint fighting off beasts (the legend of Marketa's saint is associated with a story of a battle against the dragon-shaped devil). This would have been done by the Church not only during the summer bear festival, but also during the winter bear funerals by turning attention to Henrik's hagiography. However, a comparative study of traditions reveals the original meaning and way of celebrating the annual celebrations in question.

Finally, we come to the fourth anniversary of the year, the Winter nights, that is, 12-14 October. The connection with the bear at this time is more distant than the other days, because the cattle has already been driven inside by Syys-Matti (21 September), when the bear itself began to look for a place for its winter den. So is there anything referring to the bear at this time? Perhaps, as could be expected, it can be said that there is, namely, Birgitta's day that was a week before the Winter Nights, on 7 October. Birgitta was adapted to Finnish as Pirkko or Pirjo. Some origin spells for the bear mention Pirjotar, a quick-witted wife who threw wool into the water, from which a bear was born. Kustaa Vilkuna argues for St. Birgitta's connection with the bear with the image of the door of the altar cabinet of the Vadstena monastery church, the center of St. Birgitta's cult, where a scene of Birgitta seeing the devil is shown. The image itself has been destroyed, but Vilkuna assumes that, firstly, the image of the devil looked like a bear, and secondly that the Church identified the bear with the devil. This is possible, since during the Middle Ages bear worship among Finns was still in full force and bear worship with its customs filled a cultural slot that the Church was trying to fill with its own reincarnating god. The connection of St. Birgitta and the bear also makes sense if we look at the yearly cycle from the perspective of the Year of the Bear. The bear's mother, Hongotar, has been replaced by Saint Birgitta, whose cult grew rapidly and strongly, especially after her canonization, which was on 7 October. As with all other anniversaries of the Year of the Bear, the tradition itself shows that the Christian influence has led to the obscuration of the original meaning of festive days, so also with the autumnal commemoration.

In this way, we have been able to form a unified set of annual celebrations, which in the light of tradition turns out to be centered around the bear, the son of the Sky God. That is why it is justified to talk about the calendar based on the four fixed points of the year as the Year of the Bear.

Literature and links

Elli Neidin Unelmia 2011. Tänään on karhunpäivä.

(link: https://elli-neidin-unelmia.blogspot.com/2011/07/tanaan-on-karhunpaiva.html)

Haavio, Martti 1967. Suomalainen mytologia.

Pentikäinen, Juha 2005. Karhun kannoilla: metsänpitäjä ja mies.

Tenhunen, Eeva-Liisa 1994. Ohtonen otavanpoika.

(link: http://www.aikakone.org/ohtonen.htm)

Vilkuna, Kustaa 1950. Vuotuinen ajantieto.